Change

Fashioning Gentrification

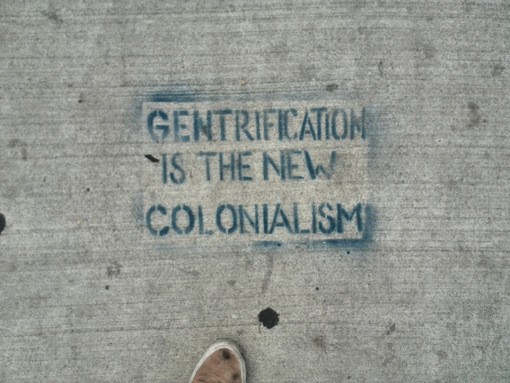

Around the word, in almost every urban centre, we’re all hyper-aware of the extensive cultural surgery that’s altering the very DNA of our cities. From London to New York to Cape Town to Berlin, aggressive gentrification (neatly repackaged as “urban redevelopment) is crippling not just the creative class, but more critically, the local communities and families that have long been established in areas now targeted by developers. How guilty are “creatives” in the process of gentrification, and how can we do more than sit back and passively watch countless people be displaced from the neighbourhoods they’ve called home for generations?

In London, gentrification essentially has an iron grip. The list of London clubs to have shuttered in the last few years is endless, house prices have risen 50% in the last 10 years, and our generation is renting their way into poverty. Yet, why does the usual discourse around gentrification seem to only bastardise the ‘hipsters’ and ‘artists’? While there is certainly a linear trend to observe that could almost be considered universal – artists move in enticed by cheap rent, the area gains ‘hype’, house prices skyrocket, the affluent people move in, and entire communities are displaced – but there is still more to this complex process than well-manicured beards and cereal cafés.

Even those first wave of gentrifiers (artists taking advantage of cheap rent) are almost always priced out when the faceless world of financiers and their market-value goals move in. Gentrification goes beyond its first visual symptoms like artisanal bakeries, but what first-wave gentrifiers are certainly guilty of is not doing enough to integrate their local communities and alienating the diverse make-up of different cultures that made these areas so unique in the first place. It’s an essential part of the gentrification process that perpetuates much more opaque, confusing and damaging processes of gentrification, instigated by the loss of social housing, regulation and the overarching control that belongs to big developers and profit-orientated landlords.

Gina Elosi, a young London-based jewellery designer tells us there are ways around it, and it is by, “recognising our collective responsibility and understanding that we’re all connected. Not only the individuals, but also the big businesses and the government.” For Elosi, it’s about not isolating yourself in “up-and-coming areas”, and defining yourself as an “other”. Can we really fight this problem by simply volunteering in local community projects, or opening up our design studios to young people who haven’t considered creative practice as a career? It might not be, but it’s certainly a start.

Though Elosi is optimistic, she’s also jaded with London’s reality. “Gentrification affects me to the point of seriously considering moving elsewhere. I feel like I can be creative here, but I spend so much time simply trying to survive. It costs so much to live here and pay bills, and with all the costs of a business on top of that, including PR, London has become a ludicrous rip-off,” says the jewellery designer.

It’s not an endemic that’s specific to London either, and any major city can probably relate in some stripe, and these rampant changes feel beyond frightening, especially when their lasting and negative effects come with such real, social injustice. For a generation of young creatives today, leaving places like London is the only option. 323,000 people emigrated from Britain last year (myself included) and with spiralling costs of living, contrasted with the perceived better quality of life elsewhere, it’s easy to see why.

Most of the time, relocating doesn’t mean you’re opting out of the process of gentrification but simply diverting your complicity elsewhere. In Lisbon and Berlin, for example, a slew of young Londoners are moving there in droves, contributing to gentrification in these cities and more pertinently, anglicising them without even trying to learn the local language. Of course, that’s a generalisation, but it’s certainly a problem in our networked, global age where it becomes so easy to disregard local histories, customs and cultures and barely acknowledge the damage our privileged presence as a creative class can do. Berlin-based designer Sintija Avotniece blames Berlin’s increasing cost of living on the incessant arrival of international ex-pats. “I think that a lot of people who come here from expensive cities like London find rooms for 500€ and think it's cheap. But NO! For Berliners, it’s not cheap and when several people actually agree to pay such high prices, it means that the general rent prices spiral out of control,” says the Latvian designer.

However, not everyone is so critical of the correlation between creatives and gentrification. Heiner Radau, a native Berliner says, “it's not the fault of creatives. They’re simply creating or trying to create something new and interesting. Of course, if there's something going on, the masses will follow. It's the law of the market: rising interest and a limited quantity of flats means rents will rise. Though, state regulated property laws would eventually be able to break this vicious circle,” says the designer. On the subject of “combatting gentrification through the arts”, Radau feels such an impetus is way too abstract. Maybe, he’s right. “Keep the bonds of the community tight and know your neighbour, not your enemy. Know the people living in your street and greet strangers, be inclusive and maintaining an open mind is a powerful weapon against losing the place called home,” he tells us.

Yet, when it really comes down to the act of creativity, gentrification is totally damning to any artistic process and particularly to fashion. How are emerging fashion designers surviving gentrification in their cities and what happens if they can’t? Can fashion ever be an agent of change in this process?

For many designers, moving to far-flung corners of the world is an exciting and liberating option. Hans Martin Galliker, originally from Switzerland, is now based in Beijing, China where he co-founded NEEMIC, a stylish and sustainably conscious fashion brand. Hans is quick to lay blame on ‘hipsters’ and ‘yuppies’ for Beijing's gentrification because they simply don’t understand or acknowledge their responsibility or complicity. “They like to indulge themselves in these neighbourhood’s new-found cultural cachet while their contribution to the local economy is often limited to a cappuccino in the fancy new 'it place,” says the designer. It’s a seemingly harsh position to take, and though Hans understands the wider mechanisms of unsynchronised development that goes beyond fixe-bikes and raw, green everything, it’s a view that’s shared by so many other NJAL designers, no matter where they are in the world.

To expand this conversation away from a Western-centric lens, it seems critical to note that Beijing was once a more affordable option for creatives and artists than Hong Kong for example. As creativity spiked in the Chinese capital in recent years, so has rent. Hans also tells us about the loss of the city’s most culturally vibrant spaces like artist commune ‘Homeshop’ and experimental theatre space ‘Zajia Lab’ due to rising rent. It’s now pretty clear that gentrification is a truly global problem. Where Londoners instinctively flee to mainland Europe's more subversive creative capitals, where’s next for Chinese creatives? Young designer Vega Zaishi Wang, is about to transplant her business from Beijing to Xiamen where rents are much cheaper, the climate is milder and not so polluted. There seems to be a global pattern emerging, but doesn’t that just mean the perpetual cycle of gentrification is endless?

While younger designers are ready to fight against the oppressive governments and corporate bodies orchestrating the wider damages of gentrification, they’re also continuing to adapt and continue to make work in alternative ways. Whether that means working an additional two jobs, or sharing studios, young creatives today simply don’t have enough time to feel bitter or nostalgic about the bygone days of cheap rents. Beyond the social injustice as a result of gentrification, young designers are worried whether art, fashion or creative practices can even survive these hostile economic realities. Perhaps the war against gentrification begins with understanding our collective complicity in encouraging gentrification and waging war against it begins on a cultural macro scale.

After speaking so many younger designers on the subject, they seem to understand there is more they can all do. Artists, fashion designers and creatives of any stripe should start treating their area’s long-standing population equally, and be involved inside their neighbourhoods cultural complex, instead of simply imposing their own agenda and assuming a neutral and passive position within the process of gentrification. Of course, the bigger change has to come from the higher echelons of power, but we can question how much are we supporting our local businesses, giving back to our communities and interacting with people who don’t look like us? Gentrification is policy, but it’s also a systematic process and there are ways to disrupt it and reclaim some control.